Contemporary fiction for teenagers is much more

controversial than when I was a child. Dark subjects such as suicide, incest, rape

and brutality are now featured in many novels directed at children from ages 12

years and up. If books show us the world, teen fiction can reflect portrayals

of what contemporary life is and how it is also portrayed in the media and in

movies. Young readers often find themselves surrounded by images not of joy or

beauty but of damage, brutality and losses of the most horrendous kinds. So

what responsibility, if any, does an author have when it comes to depicting

controversial content?

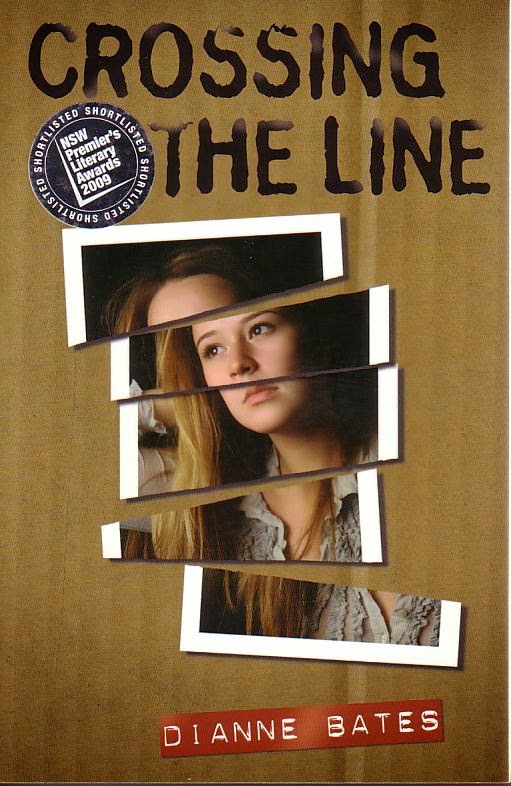

I am guilty of writing about dark subjects in my YA novels: The Last Refuge (domestic violence), Crossing the Line (self-mutilation and

stalking), and The Girl in the Basement

(kidnapping and murder). I didn’t set out to write controversial subject

matter; what I’ve written in these books, and what I write in most of my

social-realism novels generally comes from my own life experience or my

observations of and reflections on what is happening about me in the society in

which I live.

I am guilty of writing about dark subjects in my YA novels: The Last Refuge (domestic violence), Crossing the Line (self-mutilation and

stalking), and The Girl in the Basement

(kidnapping and murder). I didn’t set out to write controversial subject

matter; what I’ve written in these books, and what I write in most of my

social-realism novels generally comes from my own life experience or my

observations of and reflections on what is happening about me in the society in

which I live.

The Last Refuge,

about children who are witnesses to domestic violence, comes from my childhood

experience. I wasn’t just a witness; I was physically assaulted by my father,

as were my siblings and my mother. I didn’t know as a young person that others

suffered like this, too, at the hands of family members. If I had read The Last Refuge as a teenager, I would

have known ours was not the only family which suffered. And, too, I would have found out that there were refuges to

which women and their children could flee to (something else I didn’t know).

I was also unaware that other confused and damaged young

people cut themselves, as I did as a teenager and as Sophie does in Crossing the Line. In writing this

novel, I also drew on my experiences as a person with a mental illness (I have

bipolar disorder). This gave authenticity to scenes inside a psychiatric

hospital ward and dealings with staff, in particular with a psychiatrist who

metaphorically crossed the doctor-patient line. Was the book a catharsis? I’d be

lying if I said it wasn’t. But I’m also aware that when a book comes from the

author’s own experience, it has a genuine authenticity that an astute reader

can pick up on. When the book was released, I was inundated by adults who told

me that they had self-mutilated as teenagers, and when I spoke to teenagers in

high schools invariably there were girls who admitted knowing peers who did

this, too. I had a few letters/emails from teenage girls who confided in me

their self-harming, and so I was able to offer them comfort and advice.

I was also unaware that other confused and damaged young

people cut themselves, as I did as a teenager and as Sophie does in Crossing the Line. In writing this

novel, I also drew on my experiences as a person with a mental illness (I have

bipolar disorder). This gave authenticity to scenes inside a psychiatric

hospital ward and dealings with staff, in particular with a psychiatrist who

metaphorically crossed the doctor-patient line. Was the book a catharsis? I’d be

lying if I said it wasn’t. But I’m also aware that when a book comes from the

author’s own experience, it has a genuine authenticity that an astute reader

can pick up on. When the book was released, I was inundated by adults who told

me that they had self-mutilated as teenagers, and when I spoke to teenagers in

high schools invariably there were girls who admitted knowing peers who did

this, too. I had a few letters/emails from teenage girls who confided in me

their self-harming, and so I was able to offer them comfort and advice.

Incidentally, my husband, Bill Condon, who is a

prize-winning YA author, had a long correspondence with a teenage girl who

wrote to tell him about losing her virginity, something she hadn’t even told

any of her friends or family. She was responding to the emotional truth in one

of his novels, Dare Devils.

My third YA novel, The Girl in the Basement, was

coincidentally released the same week that the three young women escaped from

their long-term captivity in a house in Cleveland Ohio at the hands of a perverted

monster. This book’s genesis came from a newspaper clipping I’d kept for years

about a teenage girl and a seven-year old boy who had disappeared from their

respective homes some months before a Polaroid photo of the two, bound and

gagged, was discovered in a Florida car-park. Though my circumstances were

different, as a child I knew what it was like to be held prisoner to a madman

father so I was able to draw on those experiences. (And I knew how it feels to

want to murder someone!)

My third YA novel, The Girl in the Basement, was

coincidentally released the same week that the three young women escaped from

their long-term captivity in a house in Cleveland Ohio at the hands of a perverted

monster. This book’s genesis came from a newspaper clipping I’d kept for years

about a teenage girl and a seven-year old boy who had disappeared from their

respective homes some months before a Polaroid photo of the two, bound and

gagged, was discovered in a Florida car-park. Though my circumstances were

different, as a child I knew what it was like to be held prisoner to a madman

father so I was able to draw on those experiences. (And I knew how it feels to

want to murder someone!)

Whether you care if adolescents spend their time immersed in

ugliness or in beauty that is in books probably depends on your philosophical

outlook. My take is that reading about homicide doesn't turn a person into a

murderer; reading about cheating on exams won't make a kid go ahead and do this;

no teenager is going to take up smoking because a character in a book smokes,

and so on. Today’s teenagers are a part of a society in which bad things

happen. They see it first-hand in day-to-day life; they watch it on television;

they read about it in magazines and in newspapers. How they grow and develop is not dependent on

any single book they read, but it is a combination of factors, not the least of

which is the effect of the moral environment in which they are raised. Parents

have far more influence in steering a child’s passage into adulthood than any

other single factor.

Fifty years ago when I was a teenager, no-one had to contend

with young-adult literature because there was no such thing. There was simply

literature, some of it accessible to young readers and some not. Since the

1960s books have been published that deal directly with subjects such as family

dysfunction, disaffected youth, drug abuse, alcoholism and so forth. Society

has changed and those who practice in the creative arts reflect this in their

works. We cannot present life as being candy-coated when it’s not. What I hope

to do as a responsible author is to show how my fictional characters cope with

darkness in their lives and how they can emerge with solutions, and ultimately

with hope for a better life outcome.

No comments:

Post a Comment